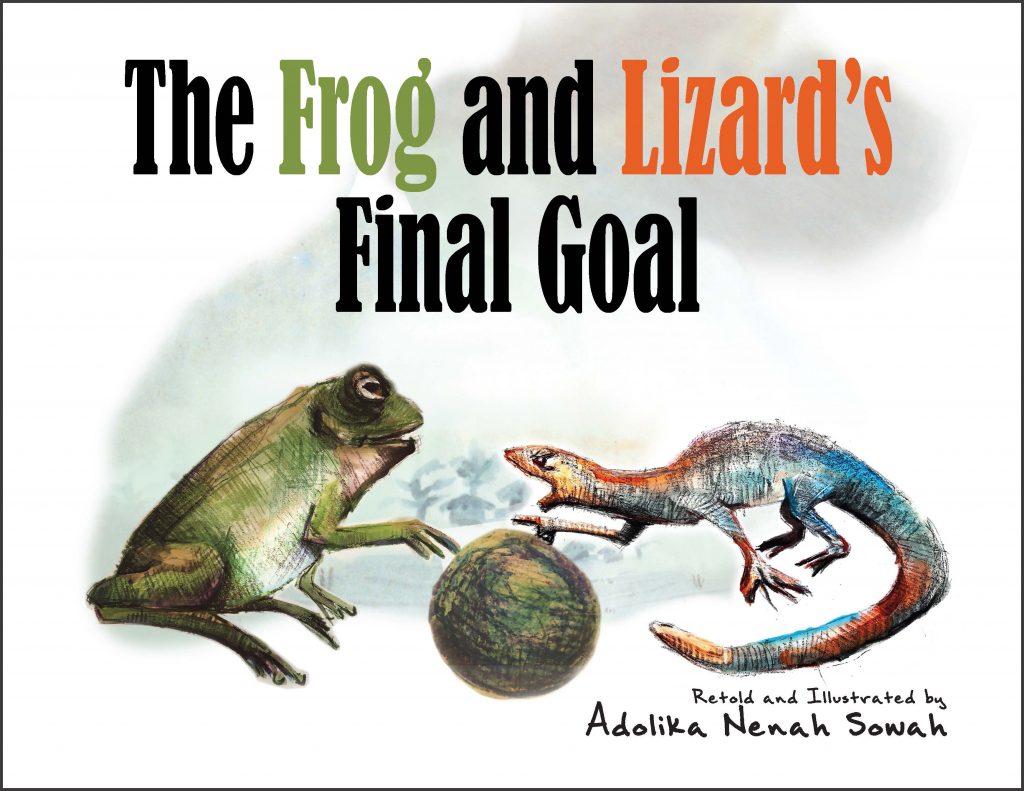

My new book, The Frog and Lizard’s Final Goal, came out in October this year, published by DAkpabli and Associates. In this book, I retell and illustrate an animal tale from Ghana.

The Frog and Lizard’s Final Goal is essentially a tale of two friends that both love football. Their friendship turns sour, when they start to fight about who plays best. Things get so heated that the two run out to a field, to face off in the final goal.

Sowah, A.N. The Frog and Lizard’s Final Goal. DAkpabli & Associates, 2021

WHY THIS STORY?

I was drawn to this simple folk story about the frog and the lizard and how the two fiends go from friendship to feud in a short time. Each is convinced, they are the best at football and are unwilling to concede in their position.

The story is very relatable.

- We’ve all had friendships that have gone sour for one reason or the other.

- Lizards and frogs are also commonly found in Accra.

- Then there is the familiar theme of football, which is immensely popular in Ghana.

Football is a huge thing here. Children, particularly boys, play it everywhere and anywhere in every little space in which they find themselves. All they need is a ball.

The picture I had in my mind for the story, was a phlegmatic frog thinking he is the best at football and his lizard friend who thinks otherwise. The quick tempered lizard escalates the conflict with his vicious counterattacks to which the frog responds in equal measure. This continues till they ran out into a field to face off for the final goal.

Sowah, A.N. The Frog and Lizard’s Final Goal. DAkpabli & Associates, 2021

WRITING AND ILLUSTRATING THE BIG FIGHT

I developed the story in stages, thinking through what each animal would say to the other to trigger an angry response. The dialogue between the frog and the lizard, would start off as playful banter and escalate to insults. I played around with different phrases. That was the fun part.

Next, I marked the points in the story I would illustrate and started sketching. The plan for illustrating had four parts. The first part was to show the two as friends. Then there is the argument and the culmination where the former friends play against each other in an open field. The last part was to show the lizard admit defeat. I executed my paintings using mixed media, using wax and watercolor on paper.

Sowah, A.N. The Frog and Lizard’s Final Goal. DAkpabli & Associates, 2021

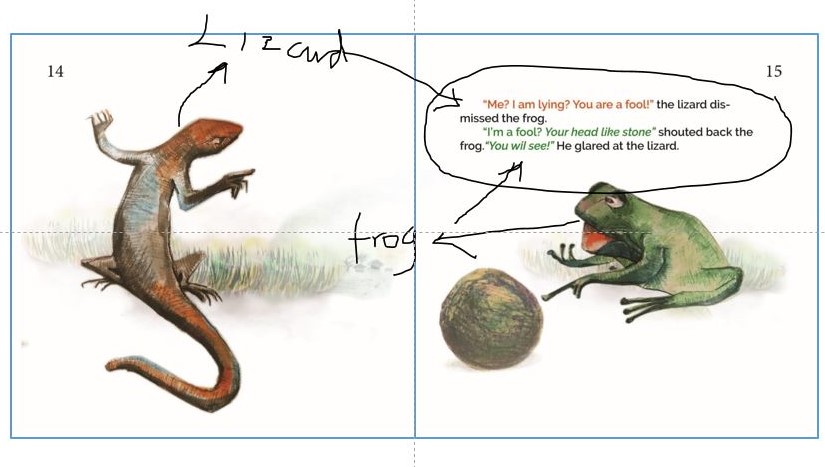

WHY IS THE TEXT IN THE BOOK, IN THREE DIFFERENT COLORS? BLACK, ORANGE AND GREEN?

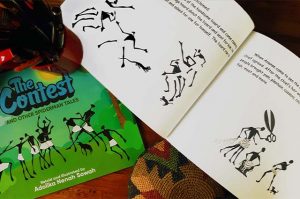

In my first version of the book layout, I intended to find ways to integrate text and illustration. I had experimented in that direction with my earlier publication titled The Contest in which I had used implied movement to integrate text and illustrations. This time, I chose to use color to bring text and illustrations together.

The color associated with the lizard is orange from the coloring on its head, neck and part of its tail. The color associated with the frog is green. I extended the colors that identified each animal into the text. The lizard’s dialogue text changed from the default black to orange and the frog’s to green.

Sowah, A.N. The Frog and Lizard’s Final Goal. DAkpabli & Associates, 2021 (p. 14, 15)

WHAT IS GHANAIAN ENGLISH AND WHY THE FROG AND LIZARD SPEAK IN GHANAIAN ENGLISH IN THE BOOK

When I read my first draft, I was unhappy with the result. The rise in conflict was believable. I am not a football fan by any means, and had done my homework and filled the dialogue with football terminology, such as dribble and header. So what was it that seemed so wrong about the work?

Out of frustration, I put aside the manuscript for a couple of weeks. When I picked it up again, I decided to read it to my then fourteen-year-old daughter. When I got to the dialogue, that is, the verbal exchange between the Frog and the Lizard, I decided not to stick to the written text, but improvise it, as my highly amused teenager looked on. This ended up as a kind of performance, where I took turns to play both the Frog and then the Lizards role. As I read out the animals’ heated verbal exchange, I realized what I was missing. It was our Ghanaian English!

Ghanaian English is a local variety of Standard British English, the official lingua franca in Ghana. Ghanaian English is widely spoken here. I realized that my earlier dialogue was too formal for the setting of the story and that the Frog and Lizard would most likely have a conversation speaking Ghanaian English, rather than Standard British English as taught in schools, for example. With this Eureka moment still fresh in my mind, I rewrote all the dialogue and grounded the story someplace in Accra.

The narrator’s voice in the story, remained in standard British English, so that there was a clear distinction between the narrator’s voice and the voices of the Frog and Lizard.

CHECK OUT A FEW COMMON PHRASES IN GHANAIAN ENGLISH

Here are a few examples of phrases commonly found in Ghanaian English. This list is extracted from the book glossary, with explanations for each.

- dier – a Ghanaian English phrase, originating from Akan and synonymous to the phrase “in particular”.

- eeiii – a Ghanaian speech expression of surprise – an exclamatory expression.

- eerrhh? – a spoken Ghanaian expression, inquiring about shock similar to “how so”.

- kweh – a Ghanaian spoken expression, originating from Ga, an exclamatory expression similar to Herrh.

- you sit there – a transliteration from Akan and meaning “to remain ignorant”. Asking someone to sit there, implies that they remain seated and refuse to embrace change.

Sowah, A.N. The Frog and Lizard’s Final Goal. DAkpabli & Associates, 2021 (p. 11)

The story came alive and I was happy with the result but I was also beset with doubts. I wondered if parents would want to buy a book with Ghanaian English for their young children.

Though Ghanaian English is spoken widely even in relatively formal settings it doesn’t appear often in fiction books for young readers up to age nine-ten. Maybe that’s because the foundation for good written and spoken skills in Standard British English is laid at that stage, say in the five to ten age bracket, and children reading Ghanaian English, with its peculiarities such as occasional lack of articles and awkward sentence construction would interfere with their mastery of Standard British English as taught in schools. Also, parents tend to look up to books for young readers as aids in teaching their children Standard British English.

Whilst as a parent, I may share part of that concern, I veer towards the position that we should take a collective risk and include more of Ghanaian English in books for young readers. In the sea of a myriad English speakers, Ghanaian English is one of the things that define us.

I think of our children who speak “Ghanaian English to each other every day. I also think of the reasonable number of parents who speak to their children in Ghanaian English every day. I wonder then, why we do not have more of it in literature for our young readers.